Hidden in plain sight

Max Planck scientists discover elusive gamma-ray pulsar with distributed computing project Einstein@Home

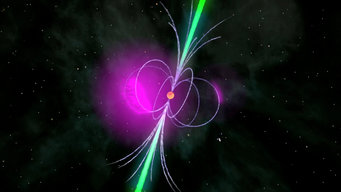

Gamma-ray pulsars are remnants of explosions that end the lives of massive stars. They are highly-magnetized and rapidly rotating compact neutron stars. Like a cosmic lighthouse they emit gamma-ray photons in a characteristic pattern that repeats with every rotation. However, since only very few gamma-ray photons are detected, finding this hidden rhythm in the arrival times of the photons is computationally challenging. Now, an international team led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute, AEI) in Hannover, Germany, has discovered a new gamma-ray pulsar hidden in plain sight in data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. The improved, adaptive data analysis methods and the computing power from the distributed volunteer computing project Einstein@Home were key to their success.

Searching for an elusive gamma-ray pulsar

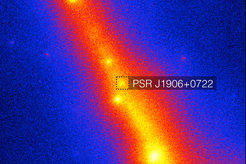

The gamma-ray source in which the discovery was made was thought to be a pulsar from the year 2012 on, based on the energy distribution of the gamma-ray photons observed by the Large Area Telescope ( LAT) on board the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. For years, it was one of the brightest Fermi-LAT catalogue sources without a known association. “Everyone believed that the source now known as PSR J1906+0722 was a pulsar. The tricky part was to show that the gamma-ray photons carry the imprint of the pulsar's rotation and arrive according to that hidden rhythm. Many had tried that before, but to no avail,” says Holger Pletsch, leader of an independent research group at the AEI and co-author of the paper that now appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The Fermi-LAT observations cover a total time of more than six years now. For every single gamma-ray photon received from the pulsar, the AEI scientists had to identify during which of the up to billions of pulsar rotations it was emitted. Since a priori there is very little knowledge about the pulsar's rhythm and its other properties, vast parameter spaces have to be searched very finely – otherwise the hidden signal would be missed. “It's a lot like searching the proverbial needle in haystack, except that beforehand we don't even know what our needle exactly looks like,” says Colin Clark, PhD student in Pletsch's group and lead author of the paper.

An adaptive search as crucial ingredient

Fermi-LAT's gamma-ray sky resolution is limited, so the sky position is not known well enough beforehand; but an offset in the sky position affects how the arrival times of the photons are reconstructed and whether the correct pulsar rotation phase can be identified for each photon. “We therefore have to search over a grid in the sky around the Fermi-LAT catalogue position. To make sure we do not miss the pulsar, we included a safety margin in our search grid,” explains Clark. “More importantly, we also made our search algorithm adaptive – even if the source was at the edge of the analyzed sky patch, the search algorithm could ‘walk away’ and still find the pulsar.”

It turned out that the new adaptive search method was exactly what was needed to get to the bottom of the riddle of PSR J1906+0722. Its actual sky position is outside the conservatively large region covered by the sky grid, which is why earlier (non-adaptive) searches did not find it. The new methods are also more efficient: They can analyze larger parameter spaces at the same computing costs.

Einstein@Home contributes computing power

Still, the computing costs required for the search are enormous: Blind searches like this one would take several dozens of years on a regular laptop. Therefore, another crucial ingredient for the discovery was the use of the distributed computing project Einstein@Home. Each week, tens of thousands of volunteers from all around the word donate otherwise idle compute cycles on their laptops and desktop computers to the project. “We are very grateful to all Einstein@Home volunteers. Their valuable contributions have made our discovery possible,” says Pletsch.

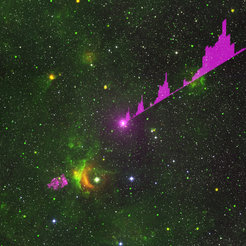

Supernova remnant and star quake

After their discovery far from the catalogue position, the scientists had an even closer look at the Fermi-LAT data, to find the reason for the offset. By analyzing only those gamma-ray photons received while no pulsed radiation from the pulsar was detected, they were able to identify a second gamma-ray source nearby. In the Fermi-LAT catalogue it had been lumped together with the pulsar into a single source offset from the true pulsar position.

“From our follow-up analysis it appears that the nearby gamma-ray source could be the shock front of a different supernova remnant slamming into a neighboring molecular cloud and generating gamma-rays in the process,” explains Clark.

Upon closer inspection, it also became apparent that the pulsar had suffered a so-called glitch in the year 2009. After the glitch, the pulsar suddenly spun more rapidly than previously and is still settling back to its old rotation rate. This sudden shift also affected the gamma-ray photon arrival times, and complicated the data analysis.

Pulsar glitches are thought to be linked to quakes in the neutron star's crust and their study might provide insights into their interior structure.

Finding otherwise invisible pulsars with “blind” searches

PSR J1906+0722 is not detectable in radio nor in X-ray observations conducted before and after the discovery. “This shows the importance of these ‘blind’ pulsar searches in Fermi-LAT gamma-ray data. Only with these searches that do not require exact prior knowledge will we be able to discover otherwise invisible pulsars. This is an important contribution towards a more complete view of the Galactic pulsar population,” says Pletsch. The combination of new data analysis methods developed at the AEI and the improved ‘Pass 8’ data recently released by the Fermi-LAT collaboration has made these blind searches more sensitive than ever before.

Background information after page break

Pulsars

Neutron stars are exotic objects. They are made up of matter much more densely packed than normal, giving the entire star a density comparable to an atomic nucleus. The diameter of our Sun would shrink to less than 30 kilometers if it was that dense.

Neutron stars also have extremely strong magnetic fields. Charged particles accelerated along the field lines emit electromagnetic radiation in different wavelengths. This radiation is bundled into a cone along the magnetic field axis. As the neutron star turns about its rotational axis, the cones of radiation sweep through the sky like a lighthouse beam because the rotational axis is usually inclined relative to the magnetic field axis. The neutron star becomes visible as a pulsar, if the beams sweep over Earth. Pulsars rotate with cycles of a few seconds up to only milliseconds. Their rotational periods can be highly stable with a precision that places them among the most accurate clocks in the Universe.

These cosmic lighthouses were first discovered in 1967 by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and identified as radio pulsars. X-ray and gamma-ray pulsars are also known to exist today. Even though not all pulsars are observable in all wavelengths, scientists assume that they still emit radiation in the entire electromagnetic spectrum. However the mechanisms which govern radiation emission in different frequency ranges are not yet completely understood.

Gamma-ray pulsars and radio pulsars

A plausible explanation why some pulsars are visible as as gamma-ray pulsars and not as radio pulsars could be that lower-energy radio waves are bundled in a tighter cone at the magnetic poles than high-energy gamma-radiation. Since radiation is mainly emitted along the surface of the cone and different wavelengths are emitted in cones with a different spread, radio waves and gamma waves would leave the neutron star in different directions. A pulsar might thus become visible as a gamma-ray or radio pulsar to a distant observer (depending on which cone sweeps across the observers position). Another model has gamma radiation originating not in the polar regions of the magnetic field but rather the equatorial plane where the field lines are disrupted. It is therefore very important to observe as many pulsars as possible in all wavelengths to better understand these mechanisms.

Einstein@Home

This project for distributed volunteer computing connects PC users from all over the world, who voluntarily donate spare computing time on their home and office computers. So far more than 400,000 volunteers have participated and it is therefore one of the largest projects of this kind. Scientific supporters are the Center for Gravitation and Cosmology at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute, Hanover) with financial support from the National Science Foundation and the Max Planck Society. Since 2005, Einstein@Home has examined data from the gravitational wave detectors within the LIGO-Virgo-Science Collaboration (LVC) for gravitational waves from unknown, rapidly rotating neutron stars.

As of March 2009, Einstein@Home has also been involved in the search for signals from radio pulsars in observational data from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico and the Parkes Observatory in Australia. Since the first discovery of a radio pulsar by Einstein@Home in August 2010, the global computer network has discovered more than 50 new radio pulsars.

A new search for gamma-ray pulsars in data of the Fermi satellite was added in August 2011. It has discovered five new gamma-ray pulsars as of today.