Stronger tests of Einstein's theory of general relativity with binary neutron stars

Combining gravitational-wave observations and pulsar timing to study alternatives to the theory of general relativity

Einstein's theory of general relativity has withstood 100 years of experimental scrutiny. However, these tests do not constrain how well the very strong gravitational fields produced by merging neutron stars obey this theory. New, more sophisticated techniques can now search for deviations from general relativity with unprecedented sensitivity. Scientists at the Max Planck Institutes for Gravitational Physics and for Radio Astronomy studied two foremost tools for testing the strong-field regime of gravity – pulsar timing and gravitational-wave observations – and demonstrated how combining these methods can put alternative theories of general relativity to the test.

Only recently, neutron stars have been observed through gravitational waves. On August 17, 2017, the LIGO-Virgo detector network measured gravitational waves from the merger of two neutron stars. These exotic objects are made up of incredibly dense matter; a typical neutron star weighs up to twice as much our Sun but has a diameter of only 20 kilometers. This year marks the 50th-year anniversary for the first observation of neutron stars, as pulsars. The precise nature of such extremely dense matter has remained a mystery for decades.

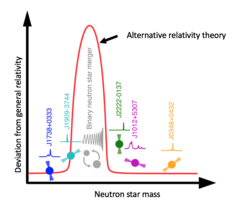

In a recent publication in Physical Review X, the authors investigated theories of gravity in which the strong gravitational fields within neutron stars differ from those predicted by general relativity. This strong-field deviation causes binary systems to radiate energy and merge more quickly than in general relativity – a behaviour that should be seen in neutron star observations.

“The gravitational acceleration at a neutron star's surface is about 2×1011 times that of the Earth which makes them excellent objects to study Einstein’s general relativity and alternative theories in the strong-field regime,” explains Dr. Lijing Shao, lead author of the study. “In a systematic investigation with pulsar timing technologies, we were able to put constraints on a class of alternative gravity theories showing for the first time in detail how they depend on the physics of the extremely dense matter they contain.” This is encoded as the “equation of state” of neutron stars which is yet uncertain.

Shao who was a postdoc at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute/AEI) when he worked on the project and wrote the paper moved to the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in September 2017. He and his colleagues studied eleven possible equations of state for five binary-pulsar systems, each of them a combination of a neutron star and a white dwarf. They discovered that the current best constraints on modified gravity from binary pulsars have gaps that gravitational-wave detectors could fill. “During the second observation run LIGO and Virgo have already proven that they are sensitive enough to detect binary neutron stars, and their sensitivity will further improve in the next few years when the Advanced LIGO and Virgo configuration is attained,” says Ph.D. student Noah Sennett, second author of the paper. “The LIGO-Virgo detectors may soon discover binary neutron star systems with suitable masses that could improve the constraints set by binary-pulsar tests for certain equations of state and thus put Einstein’s general relativity and alternative theories to a qualitatively new test,” says Professor Alessandra Buonanno, director of the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity division at the AEI in Potsdam and co-author of the paper.

Future gravitational-wave detectors like the Einstein Telescope will further improve these tests and eventually close the gap in the current constraints. Complementary tests of strong-field gravity will become a reality in the near future.